Tuberculous Imaginaries

A Media Art Installation on the History of Tuberculosis by Sean Purcell

View the Project on GitHub tuberculousimaginaries/Installation

Tuberculous Imaginaries

Artist’s Statement

Tuberculous Imaginaries is a response to a kind of medical image perpetuated, in part, by the rhetoric of the medical museum. These institutions promote a spectacular image of the human body, which sees it as something that stirs excitement and fear, curiosity and revulsion for the viewer. Whether it be early modern science’s “book of the body”, the rise of the Parisian method of anatomy and the medical library, or the contemporary posthumous sideshow of Body Worlds. An implicit product of the grand staging of the human corpse, is the issue of its sourcing—where did they acquire the organs that are sealed in spirit? And from whom did they pull the heart, bone, or sample of skin? Undergirding much of modern, western medical science is a silent actor: the patient from which knowledge, material, and argument is extracted, excised, or harvested. The bodies that would be anatomized, pathologized, and (literally) objectified were most commonly the dispossessed, the racialized other, and the most desperately ill. The patient as clinical material reinscribed and reinforced the value of the medical class, enabling medical researchers to emerge in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries (depending on which western country you examine) as an esteemed (and profitable) profession.

Tuberculous Imaginaries responds to this history by reconceiving how the primary artifact can be engaged by a public audience. Seeing museological practice as more than an enshrinement of unique artifacts and dominant histories, I have chosen to draw on various different kinds of discursive materials associated with tuberculosis research at the turn of the twentieth century.

Each projector displays a different kind of image associated with the practice of normal science. Projector A shows pathological illustrations and clinical photographs. Projector B is made up of images of laboratories, pharmacies, and patient care; each image in this feed shows the body of medical researchers and practitioners, and care has been made to single out the doctors, nuses, and scientists, to make them the focus (sometimes at the expense of the image of the patient). Projector C consists of text generated with optical character recognition (OCR) of sections from the books that were excerpted for Projectors A & B’s video feeds. Rather than enshrine these artifacts as authoritative, concrete specimens, I have taken care to respond to and reflect on the rhetoric employed by medical professionals in their discourses between other scientists and the public. I have outlined the protocol for each video feed below, following a call for codifying particular modes of critique by Max Liboiron.

My intent for this installation is not to disrupt or disprove modern medicine’s epistemics. The public good provided by medicine is significant—especially as we claw our way out of a global pandemic. My interest in this project (and with my more traditional research) is to understand how medicine produces and is produced by certain classes of people: how medicine inscribes and describes what is sickness, and how this practice reinforces certain prejudices through the practices of scientific racism and universalism.

One final note: I have attempted to short circuit the spectacular exploitation of the sick, dying, and dead patient with care to not show the patient in exploitative, dehumanizing, and humiliating positions. In a previous photo essay (and early draft of the current project which was originally called Terminal Imaginaries) I more openly displayed the patient, and the various contortions the patient experienced when made into a specimen by medical researchers. I have left some images that show the patient in this installation, but at times I actively erase their physiognomy to emphasize the position of the doctor in those same frames. My intent for this project is not to continue to do violence to those who suffered from illness and the humiliations of the clinical gaze; instead, I hope to concretely show the ways medical professionals are imaged and imagined in relation to their work.

Research Protocol

(Last Edit: 4/29/2022)

- All resources will be downloaded in full from HathiTrust. (The full corpus can be found here ). Both .pdf files and .txt files will be acquired. Upon downloading, the files will be organized in the Airtable document according to their type, with identifying information (author, publisher, year, publication city). Collections of journal articles will have each article identified separately.

- Articles and books will be flagged as to the implicit audience—scientific, lay people—or their use—advertisement, research, or public knowledge.

- As these files are organized, all images will be made into separate .pdf files. These images include (but are not limited to) clinical photographs, photographs of sanataria, clinical and anatomical illustrations, and diagrams for research and teaching. Graphs and data organized as charts will not be included. Further, any image that shows a child (under the age of 18) will be noted in the accompanying .txt file (FILENAME_IMGNotes.txt) and not separated as its own image.

- These image files will be used for the upcoming installation. They will be examined, and selects will be chosen based on their merit to describe clinical visual culture.

- A secondary concern will be to choose images that do not exploit the subject—choosing framing decisions that do less to humiliate or degrade the sitter.

- While the patient is always already exploited in these images, the intent of the installation is NOT to maintain an overt exploitation in the shape of the spectacularized medical body.

- Further, this study will be omitting non-human animal testing, so as to reduce the potential scope.

- Selected images will be made into video for projectors A & B of the installation (see Installation Protocol below).

- Once selects are flagged, excerpts from the books (provided through the .txt files) will be made to accompany these images through the use of projector C (again, see Installation Protocol below).

Installation Protocol

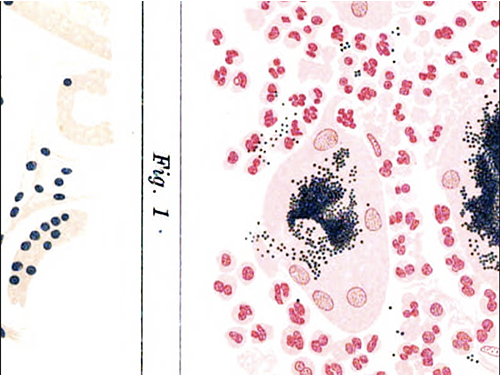

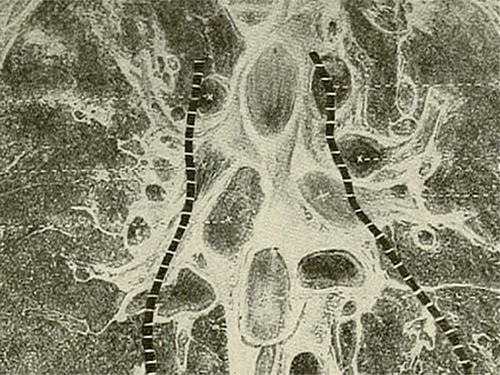

Projector A — Clinical Photographs & Illustrations

- Images will be chosen for this projector based on their use for clinical research.

- A broad collection of images will be made, to help describe the various kinds of clinical images may be levied by medical researchers. This includes anatomical illustrations, pathological illustrations, photographs of pathological samples, illustrations of microscopic organisms, and the photography and illustrations of symptoms experienced by an ailing, human sitter.

- The images will be cropped into a 1920x1080p image. While the aspect ratio may not be amenable to this, excess material will be deleted (made transparent) while the final image will remain 1080p. Once framed, cropped, and edited, the final image will be output as a .png file into the Projector A folder. (SOURCE_PAGECITATION_Draft1.png)

- The intent here is to create a generalizable image that will be more easily managed in the creation of the final video.

- These images will be imported into a video editing platform. Once uploaded, each image will be used in a slow moving zoom. The image will be made to fit a 800x600p resolution (the projector’s native resolution) and then made to do a slow zoom and fade. (Parameters: Zoom rate 100% closer over 90 seconds, fade in at the first 20 seconds from 0 opacity to 100 opacity, fade out in the last 30 seconds from 100 opacity to 0 opacity. The next image begins at the moment the previous image begins to fade.) Images will be on screen for 90 seconds each.

- After the media is made, an export will occur and the exported file will be reimported for color correction (some minor brightness and contrast adjustments to make things more clear), before being exported a second, final time.

Projector B — Imagining Medical Work

- Images will be chosen for this projector based on their connection to tuberculosis’ medical culture. They will show the relationship between the medical class (doctors and nurses) and the patient. These images will be copied from the source into the project folder (_ClinicalImages).

- My interest in this feed is to show the various ways doctors and nurses are imaged intentionally (as with posed or candid shots in laboratories) and unintentionally (as they hold patients in place for exposure).

- This projector will be placed at a 90 degree angle, and have a black space in the middle of the frame, creating space for projector C’s video feed. Images for this feed will be developed in photoshop, using a template to standardize this use of space in the image.

- Images will be selected on an ad hoc basis from the corpus, with care to show the medical doctors and nurses more so than the patients. When an image is selected, it is flagged in the folder (for ease of citation later) and fitted as best into the projector template. (This is done by a case by basis). The image, once framed in this way, is exported into a .png file labeled (SOURCE_PAGECITATION_Draft1.png).

-

Once the first image is exported, a second image using the same material is made. Using the polygonal lasso tool in photoshop any material not related to the embodied presence of the doctors is cut away and deleted, leaving a transparent version of the first image, save the embodied presence of doctors. The image is exported into a .png file labeled (SOURCE_PAGECITATION_Draft2.png). For the video feed, video material is layered as such (from the top down):

- Video Layer 8: A template for the black box that projector c will project through. - Video Layer 7: The edited (draft2) version of the photographs. - Video Layer 6: A layer for the animated block (a white rectangle measuring 800px by 20 px) - Video Layer 5: A layer for the animated block (a white rectangle measuring 800px by 20 px) - Video Layer 4: A layer for the animated block (a white rectangle measuring 800px by 20 px) - Video Layer 3: A layer for the animated block (a white rectangle measuring 800px by 20 px) - Video Layer 2: The original (draft1) framed version of the photograph. - Video Layer 1: A white matte layer. - Each image used will be edited using the same parameters (with some variation based on the images sourced and aesthetic choices). The unedited (draft1) and edited (draft2) will run for up to 80 seconds, with other effects applied to the images during this time. After 10 seconds the first of up to 4 animated blocks will move from the left of the final frame until it blocks out a part of the image (the effect will make the edited draft in Video Layer 7 pop out, framing elements of the image). Each block will be placed based on aesthetic consideration, and in the case that only 2 or 3 are warranted, the image duration will be reduced by 10 seconds. After all of the blocks are animated, a final crop effect is applied to the original (draft1) image which will crop out the images over 10 seconds (leaving the white matte and the top edited (draft2) visible). After this is cropped out, the image stays static for 20 seconds before fading out. The white matte is left visible for 5 seconds before the next image is cut into the feed.

Projector C — Rhetoric and Response

- Using images flagged and selected for preliminary use in both the projector A and B video feeds, a collection of .txt file excerpts will be made from the optical character recognition (OCR; provided by HathiTrust) processed versions of the sources.

- From here, the text will be cleaned up (removing typos, documentation that shows pagination and so on).

- Once cleaned, the excerpted texts will be read and commented upon.

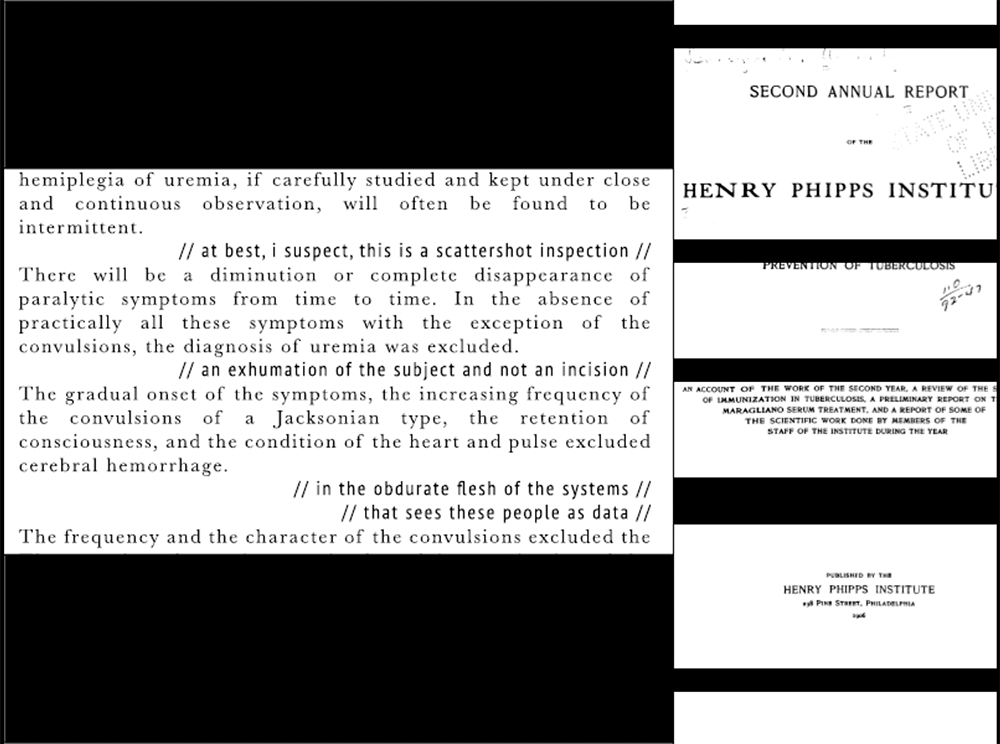

- The original text will remain the same, but occasional breaks in the spacing using the brackets of “// [comment] //” will delineate comments and interventions in the text.

- Comments are broad, but should be quippy, commenting on granular aspects of the text, assumptions, common metaphors, and noting recurring themes. Comments will also be all in lower caps (for purely aesthetic differentiation).

- Once an excerpt is commented, the text is copied into a preformatted photoshop file—(800px x 20000px ). The text is formatted as follows:

- Original Primary Text: Baskerville 16 font, left justified

- Comments: PT Sans Narrow 16 font, right align

- In addition to this formatting, the commented lines will be matched with a rectangular block, to signify disruption in the original source.

- Once finished, the file will be exported as a .png file (SOURCETITLE_ExerptNOTEONCONTENT.png)

- The final video will use the photoshopped image by placing it under a preformatted template (to fit within the requirements of projector B), this layer will then be placed over an image used to cite the text source (the cover page, the paper title, or other identifying material in the original .pdf file).

- The photoshop file will be aligned with the left part of the frame, and adjusted to better frame the text (a .7% crop on the top part of the frame). The image will move 18-20 frames up every 4 seconds (depending on variation in the source), imitating a crawl.

- Once a text file is finished, the next file will be layered over the last to make an illusion of infinite crawl.

Acknowledgements

This project would not be possible without considerable help from my friends, colleagues, and family. I’d like to thank my colleagues who participated in the HASTAC Scholars Program, especially Joie Meier and Tim Etzkorn. I’d also like to thank everyone at the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities for supporting my creative growth both as part of their institutional duties, but also as co-workers and friends, Kalani Craig, Michelle Dalmau, Vanessa Elias, Ella Robinson, Pouyan Shahidi, Maks Szostalo, and Sydney Stusman. I’d also like to thank colleagues in the Media School who have made this work possible—specifically to Mike Aaronson who has been a steadfast friend throughout the last few years. To my dissertation committee—Stephanie DeBoer, Joan Hawkins, Rachel Plotnick and Bret Rothstein—most of which were probably surprised by the materialization of this project, because I should have spent the last two months writing. Finally, I want to thank my mother and father for their never ending support for my creative endeavors (film school was a bust, and yet we soldier forward). Most of all, I want to thank Lauren, who has weathered my sleepless nights, ruminating on the project, who has nodded politely while I pontificate about some esoteric and inconsequential aspect of the design, and who has showered me with love and support as I continue to take on projects that are too big for one person to handle. I love you Lauren, and thank you for always being there.

Secondary Sources Cited

Alberti, Samuel J. M. M. 2011. Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blakely, Robert L., and Judith M. Harrington, eds. 1997. Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Cartwright, Lisa. 1995. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Curtis, Scott. 2015. The Shape of Spectatorship: Art, Science, and Early Cinema in Germany. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 2016. “Photography and Medical Observation.” In The Educated Eye, edited by Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 68–93. Hanover: Dartmoth College Press.

Dijck, José van. 2005. The Transparent Body: A Cultural Analysis of Medical Imaging. Seattle & London: University of Washington Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1994. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books.

———. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Hallam, Elizabeth. 2016. Anatomy Museum: Death and the Body Displayed. London: Reaktion Books.

Knorr Cetina, Karin. 1999. Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1986. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Mitchell, Robin. 2020. Vénus Noire: Black Women and Colonial Fantasies in Nineteenth-Century France. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Purcell, Sean. 2022. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen. Link to Article

Redman, Samuel J. 2016. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard Unievrsity Press.

Richardson, Ruth. 1987. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Sappol, Michael. 2002. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sontag, Susan. 1990. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

———. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Troyer, John. 2020. Technologies of the Human Corpse. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Waldby, Catherine. 2000. The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine. London & New York: Routledge.

Warner, John Harley. 2014. “The Aesethetic Grounding Of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88 (1): 1–47.

Washington, Harriet A. 2006. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black American from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Harlem Moon & Broadway Books.

Primary Sources Cited

Annual Medical Report of the Trudeau Sanatorium and the Thirteenth Medical Supplement for the Year Ending October 31, 1917. 1917. The Trudeau Sanatorium. Available on HathiTrust

Atkinson, Charles E. 1922. Lessons on Tuberculosis and Consumption for the Household. London & New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. Available on HathiTrust

Baldwin, Edward R., Lawrason Brown, M. J. Rosenau, H. R. M. Landis, Henry Sewall, Paul A. Lewis, Borden S. Veeder, and Allen K. Krause, eds. 1917. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 1. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

———, eds. 1919. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 3. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

———, eds. 1920. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 4. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

———, eds. 1921. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 5. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

Baldwin, Edward R., Lawrason Brown, M. J. Rosenau, Henry Sewall, Paul A. Lewis, Borden S. Veeder, and Allen K. Krause, eds. 1918. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 2. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

Carmody, T. E. 1909. The Differential Diagnosis of Lesions of the Mouth Due to Carcinoma, Sarcoma, Syphilis and Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanatarium Monthly Bulletin. 1917. Vol. 1–4. City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium. Available on HathiTrust

———. 1925. Vol. 5–6. City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium. Available on HathiTrust Crofton, W. M. 1917. Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co. Available on HathiTrust

Densmore, Emmet. 1899. Consumption and Chronic Diseases: A Hygienic Cure, At Patient’s Home of Incipient and Advanced Cases. London: Sonnenschein & Co. Available on HathiTrust

Fishberg, Maurice. 1916. Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Philadelphia & New York: Lea & Febiger. Available on HathiTrust

Gravesen, J. 1925. _Surgical Treatment of Pulmonary and Pleural Tuberculosis. New York: William Wood & Co. Available on HathiTrust

Hall, Freeman. 1912. Tuberculosis and Allied Diseases: An Account of Their Origin and Treatment from the Earliest Times up to and Including the Present_. Kalamazoo: Yonkerman Company. Available on HathiTrust

Hamilton, James A. 1925. Pneumoconiosis—Three Cases Two of Silicosis, and One of Anthracosis with Tuberculosis Superinduced. Complete Histories with Temperature Charts, X-Ray Pictures and Colored Plates of Lungs. State of New York Department of Labor Bulletin. The Division of Industrial Hygiene. Available on HathiTrust

Hawes, John B. 1913. Early Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment. New York: William Wood and Company. Available on HathiTrust

Krause, Allen K, J. Burns Amberson, H. J. Corper, Edward R Baldwin, Lawrason Brown, H. R. M. Landis, and Paul A. Lewis, eds. 1924. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 10. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

———, eds. 1925. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 11. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

Krause, Allen K., Edward R. Baldwin, Lawrason Brown, H. J. Corper, H. R. M. Landis, Henry Sewall, Paul A. Lewis, and J. Burnes Aberson, eds. 1923. The American Review of Tuberculosis. Vol. 8. Baltimore: National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Available on HathiTrust

Lockard, Lorenzo B. 1909. Tuberculosis of the Nose and Throat. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Medical Book & Publishing Co. Available on HathiTrust

Maylard, A. Ernest. 1908. Abdominal Tuberculosis. London: J. & A. Churchill. Available on HathiTrust

Mays, Thomas J. 1901. Pulmonary Consumption, Pneumonia, and Allied Diseases of the Lungs; Their Etiology, Pathology and Treatment, with a Chapter on Physical Diagnosis. New York: E. B. Treat & Company. Available on HathiTrust

Otis, Edward O. 1920. Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Handbook for Students and Practitioners. Boston: W. M. Leonard. Available on HathiTrust

Pottenger, F. M. 1908. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. New York: William Wood and Company. Available on HathiTrust

———. 1917. Clinical Tuberculosis. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Company. Available on HathiTrust Volume 2 on HathiTrust

Report of the Henry Phipps Institute for the Study, Treatment, and Prevention of Tuberculosis. 1906. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Henry Phipps Institute. Available on HathiTrust

Riley, W. H. 1897. Report of Fifty Cases Illustrating the Successful Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Modern Medicine and Bacteriology Review. Available on HathiTrust

Senn, N. 1893. Tuberculosis of Bones and Joints. Philadelphia & London: The F. A. Davis Co. Available on HathiTrust

Walsham, Hugh. 1903. The Channels of Infection in Tuberculosis: Together with the Conditions, Original or Acquired, Which Render the Different Tissues Vulnerable. New York: William Wood and Company. Available on HathiTrust